How to sell FMCG in IRAN

OW TO SELL FAST MOVING CONSUMER GOODS

IN IRAN’S FRAGMENTED RETAIL STRUCTURE

“What a mess! How can I present my brand in this shop stacked with products until under the roof and without any order?” exclaimed one top manager of a multinational producer of personal care products when entering a baqali, a traditional Iranian retail store on a market visit to explore the opportunities of the Iranian market. “Our ability to sell and distribute to more than 100.000 small stores is a tremendous asset and our advantage in the fight for market share. It constitutes a formidable entry barrier for newly arriving international competitors” declared a sales director of an Iranian dairy products producer to CERTIUS, a consultancy which helps foreign companies enter and build business in Iran, and Iranian companies improve sales, marketing and export operations. These two statements neatly sum up what the idiosyncratic structure of Iran’s grocery trade means to different people: a barrier to market entry, a challenge to overcome in order to have a chance to succeed, and an opportunity to leverage competitive advantage and defend versus new market entrants.

So how exactly is this retail structure and which challenges does it pose to fast-moving-consumer-goods (FMCG) companies? First of all, the structure of Iranian retailing is highly fragmented with huge numbers of independent stores and this is something which many Western companies find difficult to cope with. The question, which many companies ask themselves, is how to sell and distribute to as much as 300.000 small stores and vendors. Secondly, shops are small – the average store size of baqalis is 48 sqm – and therefore shelves are crammed with products without much order and without paying heed to what producers call the “picture of success”, the blueprint of how to put order in the shelf and present brands in an appealing way to shoppers in order to maximize sell out and shelf productivity. Let’s look at those two challenges in detail.

Iranian retailing is dominated by traditional trade

91,5% of all grocery trade sales is done by around 300.000 small and independent stores, commonly called “traditional trade”. Only 8,5% of total market sales go through hypermarkets, supermarkets and discounters – organized chains of stores and “modern trade” formats which in Western countries have become the norm during the last 70 years but of which Iran boasts only about 800 stores.

The number of 300.000 traditional trade stores includes 175.000 small grocers and 118.000 specialized stores, such as kiosks, bakeries, protein stores and the like. So the first challenge is how to reach these vast numbers of stores. Western manufacturers who are used to highly concentrated trade structures find it difficult to get their products cost-efficiently into that many stores (we call this “how to achieve coverage”). Unless, that is, they are used to selling in a traditional trade environment which is prevalent in countries like Mexico or Russia too.

Due to their limited size of an average 48 sqm sales area and very small storage areas the typical traditional trade store carries a limited assortment which reduces FMCG brands’ chances to present an appropriate choice of variants and formats of their products. Shopkeepers want to increase the productivity of their stores by cramming in as many products as possible. But modern concepts of shelf productivity maximize sell out and shelf productivity by exactly defining the SKUs (formats, variants and packaging sizes of any given product) sold in the store based on a thorough understanding of shoppers’ purchasing motivations and behavior and a good deal of number crunching of past sales patterns. Those products are then arranged in a way which, again based on complex analyses plus some simple rules, maximizes the number of shoppers’ purchasing acts and directs shoppers’ attention to a manufacturers’ strategic SKUs. The optimal product presentation in shops, the “picture of success” basically consists of presenting the right SKUs (“Must-Stock-SKUs”) in the right pattern (called a “planogram”) and it serves to maximize shoppers’ purchase volume or value and thus increase productivity of the shop and the manufacturer. Together with a range of other techniques, such as impulse placements, this is commonly referred to as “brand activation at the point of sale”.

Again according to CERTIUS research, this is something which professional sales managers and their field sales forces find highly difficult to get into the heads of shopkeepers who feel they know best what and how to sell.

Consumers, called “shoppers” when doing their shopping, use baqalis for nearly daily shopping trips and often follow shop keepers’ recommendations about which brands to buy. So, manufacturers’ sales visitors first have to convince the shopkeeper who actually is the first and most important bottleneck and influencer of consumers’ buying decisions. Most manufactures try do this by offering shopkeepers nearly constant discounts or free products

when they buy a certain quantity or order value. Sales professionals call this “sell-in promotions” because they help to sell products “into” the store but do nothing to “sell them out”, i.e. they do not achieve an increase in consumer purchases. This is a rather ineffective sales tool as it gets the shopkeeper used to constant discounts, which cost manufacturers a lot of money without achieving much in the end. Due to shopkeepers reticence it is extremely difficult for manufacturers, and therefore rare, to run “sell out” promotions in these stores. Even the simplest promotion types, such as a discounted shelf prices, which entice consumers to switch brands, or multipacks, which make shoppers, buy more, are extremely difficult to implement. Which is why most of the sales strategies and tools used in modern trade don’t make much of an impact in Iran’s small stores.

Modern trade, the challenge for Iranian FMCG manufacturers

Modern trade is a wholly different story. Iran’s modern trade sector which accounts for 8,5 % of total grocery sales but is growing fast, is dominated by three main formats: hypermarkets, currently 12 stores in Iran, with the main player Hyperstar (owned by Majid Al Futtaim and thus partly by French Carrefour); supermarkets, now 438 stores with main trade labels being Refah and Shahrvand; and 328 discount stores with Turkish Cambo and Golrang’s Ofogh Koorosh (a “soft” discounter) leading the segment. While some of the players enjoy extremely high store productivity – Hyperstar’s Tehran store is one of Carrefour’s global top sellers – CERTIUS does not expect a dramatic shift of market share from traditional to modern trade in the mid term. Government policies, high real estate costs and deeply entrenched shopping habits result in a slow and long-term shift, completely unlike the fast rise of modern trade in Central and Eastern Europe in the 1990ies.

Selling profitably to modern trade requires different techniques and capabilities and many Iranian FMCG manufacturers lack them. Frequent complaints that selling to modern trade is “expensive” because they ask for high discounts and long payment terms pay testimony to many local manufacturers’ lack of knowledge and sales tools. This is where Western producers are at their best, applying time-honed skills and experiences in key account management, condition management or category management. Building category growth plans and implementing them together with retailers in a data driven and concept-framed manner is paramount to successfully selling to modern trade players. It is all about “growing the cake” -increasing the market share of the retailer and with it the manufacturer’s sales – instead of “dividing a small cake” – haggling over discounts, boni, advertising contributions and countless other ways to shift profits from producers to modern trade retailers.

To reach or not to reach the traditional trade stores, that’s the question

Even the biggest Iranian distributors (sales and distribution companies to which both Iranian and foreign manufacturers often turn) rarely reach more than 100.000 stores (notable

exceptions are Golpakhsh Aval with a coverage of 145.000 or Sayasaman with 120.000) with the bulk of them covering only 40.000 to 60.000.

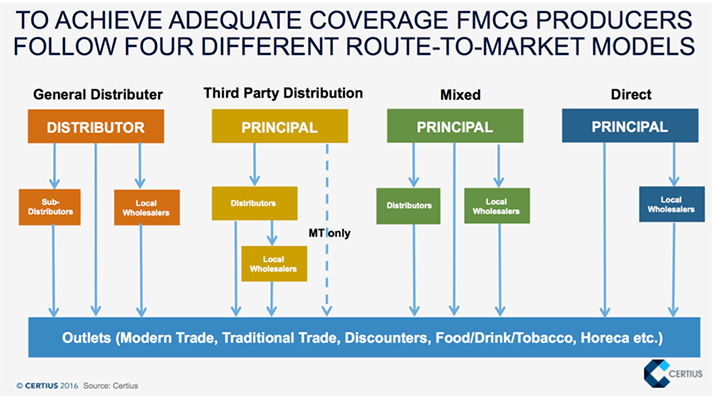

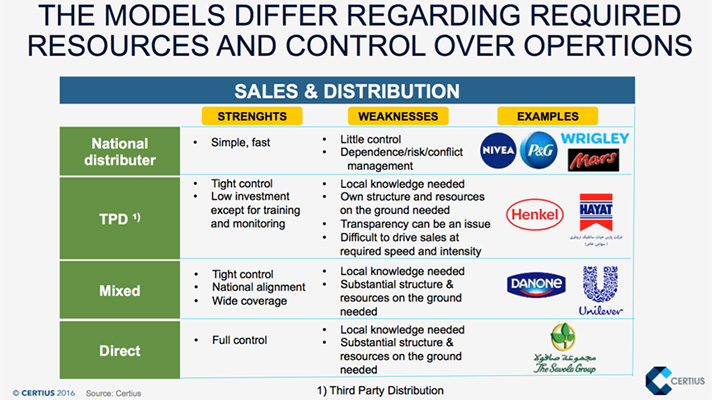

But entrusting your brands to a general distributor is only one of four main Route-to-market models commonly used by manufacturers in Iran. The other are: Third Party Distribution, where a manufacturer or importing brand owner works with a number of distributors and often serves the modern trade directly with his own organization; the Mixed RTM model by which the brand owner directly serves some trade channels or geographical areas while working with distributors and local wholesalers for others; and finally the Direct RTM model in which the brand owner does all sales and distribution with his own resources.

Each one of these models has distinct characteristics, advantages and disadvantages and each requires a different level of involvement and resource deployment by the brand owner (see chart below).

Choosing the right RTM model for your business, if you are entering Iran or scaling your current operations, requires a series of steps: first decide your business ambition and strategic objectives as the framework for everything else; then define your market entry strategy and the sales and distribution strategy; on this basis choose the best RTM model, assess potential distributors and partners, choose the most adequate one and negotiate a clearly defined agreement with business KPIs and a Service Level Agreement; then deploy your own resources, e.g. to support and monitor the distributor, and monitor execution. Finally, be prepared to adapt and change your RTM model in line with changing market circumstances and evolving business needs. Unilever Iran is a telling example. In the early 2000s the company started importing while a national distributor did sales and distribution. A few years later Unilever established its own operation and changed the distributor. In

2005 the company started to move to Third Party Distribution and today they run a Mixed RTM system.

Activating brands at the point of sales in traditional trade

Great brand activation generates sell out and thus higher profits for both shops and manufacturer. Doing this in traditional trade is not easy but it can be done, as leading companies, such as Pepsi or Danone show. The first step is to gain a sound understanding of both the shopper and the retailer. Standard research tools available in Iran include shopper studies and path to purchase analyses. Secondly, companies must set a sound basis by offering shops competitive trade margins, commercial terms and payment terms. The third step consists in defining a fact based and strategic category plan. For the traditional trade this means a number of simple elements, such as Must-Stock-SKU lists per customer class (In order to focus efforts it is useful to divide shops into customer classes based on current sales performance and future potential), simple planograms, in-store merchandising, and sales force financial incentives in part tied to the implementation of category plan specifics. To ensure proper brand visibility a brand might revert to shelf rental (paying top customers to occupy and manage a certain amount of shelf space), in-store product displays optimized for the traditional trade, and promotional staff paid by the manufacturer but acting in top stores to engage shoppers and generate purchase or trial of the brand.

No miracle cure but not mission impossible either

Selling FMCG successfully and efficiently in Iran’s idiosyncratic retail structure is a complex endeavor, both for Iranian and for international companies. Iranian producers’ success in the new age of increasing competition depends on acquiring and improving relevant capabilities and on anticipating foreign competitors by analyzing and implementing global sales best practices. Attracting much desired foreign investment to Iran will only happen if foreign brands learn how to navigate the intricacies of the Iranian retail structure. Both tasks are not without difficulty but clearly possible. Not undertaking them means to risk failure.

Source: Certius